THE TIMEWORN BEAUTY OF ASMARA, ERITREA – The New Yorker

By Gideon Jacobs Much of what we create—clothing, furniture, buildings—is plotted with an eye toward an imagined future. More often than not, we imagine that future incorrectly. Eli Durst’s photographs frequently capture traces of a yesterday

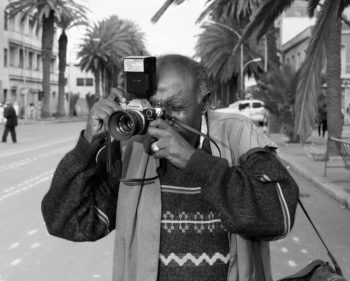

It makes sense, then, that in Durst’s first major project shot outside the U.S. he was drawn to Asmara, Eritrea, a rich but worn time capsule of a city. Italian colonizers long ago filled the city with fantastical modernist and futurist architecture. Now the surreal urban landscape houses the visual tropes of modern African life within an aesthetic imported from early-twentieth-century Europe, all of it presided over by the country’s repressive single-party government. Durst’s plan was to focus on Asmara’s unique cityscape, but, upon arriving, he discovered that the past’s hold was weakening in unexpected ways. “Several of the buildings that I had read about in architectural surveys had been closed for years, and an entire war memorial at a major intersection was just gone,” he told me. “When I asked a pedestrian what had happened to the monument, I was told that I shouldn’t ask such questions.” The authorities’ erasure of historical remnants is inscrutable and unpredictable. So Durst focussed on the people he met, using Asmara’s buildings as “markers of the past” that can “obscure the contemporary realities of life in one of the world’s poorest countries.”

The result is “In Asmara,” a body of work that has been awarded the 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize. Every photograph in the series contains signs of both vibrancy and decay. When Durst photographs breakfast, the table is warped but the coffee is fresh. When he shoots a dilapidated cinema, we assume that the theatre has long been out of order, only to notice an audience member lurking in the shadows; the image was, in fact, taken during a showing of the “G.I. Joe” sequel. As a whole, the series is an assured, understated study of juxtaposition in a city defined by its cultural incongruities. “In Asmara” is a profile of everyday Eritreans but also of the city itself, filled with bustling life and fading fragments.

k.tewolde December 27, 2016

It is my home,my city that I was born and grew up in,a large piece of me still lingers there and so are many Eritreans like me who have lost their longing to go back there because of the very people who are running the place.It is not only the relics of that besieged city is being destroyed by the junta who resides comfortably there,but also the older residents who can tell the story have fled or wiped out at the hands of the gangsters.Today the only story coming of that city is power outage,long bread lines.crumbling historical buildings,shortage of medicine and medical supplies,flight of refugees……….last but not least,the constant,mundane propaganda of of the glory days of yesteryear by the one party sponsored eritv. This grim spectacle is coming to an end sooner or later but its ugly scars will remain seared in our memories for generations to come.

zeray December 28, 2016

A child of an abuser parent asks the court to become independent. He is granted his wish and he is an emancipated minor. 30 yrs later the child is as abusive as his parent (savage evil ghedli). There are conflicting reports on the parent : some say he is reformed (as he claims “unashamedly” he was born and grew up in a modern/advanced city and not from the savage evil ghedli bush), some say he is still the same old savage abusive crank (just like his savage evil Islamic criminal ELF parents), he just has redirected his abuse to new gullible victims.

Similarly here again, we have a crippled criminal ELF whore mouth fanatic propagandist still hallucinating but not accepting responsibility and blame for creating a ghost nation called Eritrea where all her people especially the young run away from their “liberators” so-called tegadelti mothers and fathers. In other word, when are you going to stop the sweet words, fake lecturing, philosophising and all your diKhala acts? You should simply come out of your savage evil Islamic criminal ELF past and your fox hole hiding and just apologize to the people of Eritrea especially the poor peasants that you robbed and made their lives a HELL.

k.tewolde December 28, 2016

Zeray, who gave you this trashy assignment and how much nacfa do you make a month? just curious.

zeray December 28, 2016

K.Tewolde, doubly curious, exactly the same savage evil moslem amount of Saudi Arabian Riyal that you were paid to destroy Eritrea that’s much I am getting paid by the people of Eritrea to expose your savage evil criminal Islamic ELF hypocrisy, cowardice and treachery to our people.

Son of a whore and wedi Amate berad diKhala ELF whore mouth, I would be more than happy to give you more of your same diKhala’s medications on request so don’t hesitate to contact me for more sweetie treatments.

Sol December 28, 2016

K.tewolde, this Zeray who uses many IP names after accomplishing his mission on destroying asmarino.com last year moved to assena to do the dirty job of the mafia regime but these days it seems his employers are blaming him for taking long time on destroying assenna the reason which drove him crazy and to abslute vulgarity. If all assenna followers ignore him he will be completely insane and he will kill himself.

k.tewolde December 28, 2016

They are dubious characters,they don’t come clean,do they? regardless we will continue our national discussion on this medium despite their desperate artifacts.Thanks Sol,Merry Christmas and happy new year.

zeray December 28, 2016

Sol aka andom, adhanom, Zafu, WediHagher – WediHalima, Mohammed, Khalid, WoBawzan, comedian Ali, Abdurobo TeraAraA, Mehari Woldegabir, eyob tesfalem, wediSaho dead rat crock, in short, super moslem nefaHito, the rootless Yemeni immigrant nomad savage Arab dog. Ignore me??? Mefitotey reKhebku tibil your stinking fat dog Halima mother who conceived you from savage evil moslem wild Yemeni dogs on top of the Adwa and Shire/Sheraro wild dogs.

WediHalima & Wedi Various(Tigrayan + Arabs) savage evil moslem dog, we fully understand why you have to bark non-stop with different sounds and colors and we also feel sorry/forgive you for being a damaged diKhala for life beyond repairs moslem dog. After all your negis savage evil criminal Mohammed asshole was just like yourself a savage evil liar, crock, paedophil, slave trader sheyitan diablos, in short, not a great example to you savage evil moslems and savage evil moslem Arab/Tigrayan immigrant dogs.

hp December 28, 2016

Bravo SOL, i agree to your idea.

zeray December 28, 2016

Why is the rootless immigrant and ignorant savage evil moslem nomad often depicted as the most backward human being/savage Arab dog? Could it be because as a result of drinking “lots of savage evil Arab dog’s milk” or could it be because of savagery mating with his goats, camels and dogs that will keep him as a poor but still savage evil moslem half-human and half-animal. Wedi Halima savage evil Arab dog and paedophile like criminal father negis evil savage thief Mohammed, go back to your savage evil past of mating with your animals and little moslem dog daughter and cousins before you are burned alive and sent to rot in your savage evil moslem hell where you and all your vicious Islam’s cancer belong and come from in the first place.

AHMED SALEH !!! December 28, 2016

Mr. NEFAHITTO with multiple nicknames

From day one you weren’t part of JUSTICE SEEKERS movement nor HGDF supporter . You are entitled

to bark on wrong tree depending on deluded mindset with false beliefs that contradicts facts on the round.

People like you have personal issues deep down in themselves and their hidden feelings of inferiority

caused them to be as dangerous as a snake to attack venomously anyone on their path .

In real life such kind of person pull you down into violent outburst . Whatever wrong with him ASSENNA

STAFF must protect its standards from destructive comments .

For some reason their negligence might effect the hard earned rating of this forum by allowing some

morons whose motives had been to undervalue our forum .

SILENCE ALSO HAS ITS OWN LIMIT OTHERWISE LEARN FROM ITS PAID PRICE IN OUR STATE AFFAIRS .

AHMED SALEH !!! December 28, 2016

PARDON ME BROTHERS/SISTERS

THIS IDIOT MADE ME LOST FOCUS TO SAY HAPPY HOLIDAYS TO YOU ALL .

zeray December 28, 2016

Savage evil moslem WHORE/PIMP aregit kelbi areb – fagnatura Arab’s dog, are you not being pig/dog headed when you say “lost focus or begging for pardon” !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Cut all your cheap gurras, tahidid, ab TiraH maAkorika show offs especially for an evil savage Arab dog biggest beggar (mind you, from Western Christians) lemani wedi lementi goHaf rootless immigrant mushmush aregit moslem WHORE Arab dog. Just wash your stinking aregit fagnatura ass 5 times and prepare it for hard drilling by your savage evil barbarian moslem Arab slave masters even though they are finding you too old and too poorly fed to touch you but don’t give up aregit saHsaH kelbi areb.

zeray December 28, 2016

Indeed, we all know how much your savage evil criminal thief and paedophile Mohammed was also a NEFAHITO and just as ‘Raza nay abuU Haza’, savage evil aregit kelbi areb – the stinking old moslem Arab dog ahmidin salihidin WHORE/PIMP nay abuU Salih & Hawu Omar Hazo. Your savage evil Salih dog father was quite the biggest moslem whore shit.

The most ignorant savage evil mushmush aregit stinking moslem Arab dog, when are you going to stop talking from your savage evil severely damaged fagnatura backside that is corrupted and drilled beyond normality by your savage evil barbarian moslem Arab slave masters? Born the biggest moslem beggar/lemani goHaf & dying beggar demented goHaf.

Libi mushmush rootless mercenary aslamay Tiwiyiway, in English, crocked/twisted like a savage evil moslem heart, we don’t like or trust the cancerous savage evil moslem Arab dogs the illegal immigrants as they suffer from severe treachery, ignorance/inferiority complex, jealousy, obedience to the vicious cancer Islam and savage evil barbaric moslem Arab slave masters. Wedi savage evil Islam aregit mushmush WHORE Arab dog rot in moslem hell.

WediHagher December 28, 2016

Teclay, Zeray and so many nicknames, but the beast is the same old Dirbay, ex-Baal Beles from Tigray.

Merry Christmas to all of you.

Long Live our beloved Eritrea

zeray December 28, 2016

WediHalima savage evil moslem Arab dog and mother dog Halima fucker, we know your poor mother Halima and your savage evil moslem dogs sister of Fatima, SaEdu, Khedija are selling all the beles during the day time and being prostituted and savagely fucked up by old Arabs and DemHit dogs by night. But at least they are better as they are not selling their savage evil bodies and beles in your old Shires, Adwas or Mekelles of Tigray.

Deki negis savage evil criminal Mohammed whether the moslem Arab dogs men or the moslem Arab dogs women are all the same stinking cheap sheramut whore dogs of barbaric Arab slave masters. Wedi savage evil moslem Arab dog Saho dead rat crock, just rot in your moslem hell.

PH December 28, 2016

Once was a great beautiful city modern and contemporary style of Italian piccola roma. in that city grew up many asmarinos .the symbolic city of Eritrea but also the gost city in Africa and for some reason Italians are also unknown despite they design it.

zeray December 28, 2016

Savage evil ignorant, rootless moslem Arab dog, I don’t really know whether to cry or keep laughing on your extreme ignorance/arrogance and savage evil moslem gimmicks? I know you are born so thick and so ignorant like your savage Yemeni dogs, camels and TebeKhis but surely you can’t be that thick, ignorant and being savage evil moslem Arab dog for life, can you?? Stop drinking the savage evil poisonous moslem dog’s milk straight away savage moslem Arab dog!!

You should really not be pushed to scribbling nonsense but instead should be guided to read your savage evil criminal Quran, vicious cancer Islam, stop animal mating, drinking dog’s milks and above all read about the dangers being a paedohile like savage evil Mohammed to your own daughters and cousins you savage evil moslem Arab dog.

k.tewolde December 28, 2016

Folks, unfortunately this is one of the many sad outcomes from HGDEF”s rule in our beguiled homeland- a mutated human specimen,it will be a daunting task to fix it.

zeray December 29, 2016

Son of a whore, wedi Amate berad mushmush diKhala asshole lemani goHaf, why are you so desperately calling/begging for deki Halima the savage evil moslem Arab dogs to come to your rescue?? Deki savage evil cancerous moslemArab dogs will be hiding in their Saho, Yemeni rat/snake holes indefinitely so just come out and tell us how much “pure” Christian you are and also how much “pure Wedi Asmarino city” crap bullshit you are and I promise you’ll be forgiven and accepted as one of our own crock!!!!

Asmara Eritrea December 29, 2016

Reading the chain of exchanges above, it makes me think perhaps we Eritreans deserve Isiais’ brutality. As the old saying goes, a country gets a leader it deserves. If we cannot agree on trivial things, what hope do we have to remove the evil dictator? Let’s bury the crap stuff and agree on the issues that matter i.e. rule of law in our country and the removal of the beast in Asmara.

1991 will go down in Eritrean history as the year of liberation by the masses and the start of enslavement of the masses by on individual. Let’s hope 2017 will be the year we bury our differences to free our country once again and burying the dictator instead.

Eritrea forever, death to dictatorship.

koubrom December 29, 2016

Her we go again all the MAKELISTA from abay Tigray claiming asmara,

You should for your adwa ,axum, temben, shire ,

Asmara is for us eritrean

Aye Beal tiway mengedom tiwiyway kkkkkkkkk