War Over a One-Horse Town

By FRANK JACOBS About 125 millennia ago, the southern end of the strait between Africa and Arabia was much narrower, and may have been the springboard for one of early humanity’s great migratory leaps. [1] A

By FRANK JACOBS

About 125 millennia ago, the southern end of the strait between Africa and Arabia was much narrower, and may have been the springboard for one of early humanity’s great migratory leaps. [1] A big deal for everyone who has come along since, but the question of where, exactly, those first people out of Africa came from matters immensely to two very antagonistic neighbors. At this moment, in some Internet chat room, the locals are fighting over the nationality of those Red Sea pedestrians: did they originate in Eritrea, or in Ethiopia?

Hyperbole perhaps, but not by much. Few countries harbor as much mutual enmity as Ethiopia and Eritrea (which won its independence over the former in 1993, after a 40-year struggle, by helping to topple Ethiopia’s military junta), and they haggle over the seemingly smallest distinction. Pedigree, both personal and national [2], is a prominent subject in the war of words between these East African nations, across a border that, several years after they stopped fighting, is still “hot,” relatively new and fiercely contested.

The region’s recorded history goes back to 2500 B.C., when it was known to the Egyptians as Punt [3]. In the intervening centuries, countless empires rose and fell, their legacies providing ample ammunition for today’s competing national narratives. Even Balkan grudges, most of them merely centuries old, pale in comparison.

In a region steeped in history, Eritrea’s “newness” is used as an inculpatory argument — proof of its artificiality. Eritrea was a European imperialist creation, the Ethiopian line of reasoning goes, snatched from a united Ethiopian Empire by Italy’s imposition of the Treaty of Wuchale in 1889. The deceptive Article 17 of that treaty [4] led to the First Italo-Ethiopian War, from 1895 to 1896 — and a win for Ethiopia, the only victory of a native African state over a modern European one in modern history.

The resulting Treaty of Addis Ababa, signed in 1896, secured Ethiopia’s independence, but confirmed the loss of Eritrea. How great a loss, though, was never precisely defined. The border between Eritrea and Ethiopia may have been delimitated (i.e., defined by treaty), and subsequently delineated (on maps, at several occasions into the early 20th century), but never even tentatively demarcated (indicated on the ground with markers, signs or fences) [5]. Since Ethiopia effectively absorbed Eritrea after a defeated Italy ceded control of it after World War II, the border wasn’t really an issue. With an armed, independent and unfriendly Eritrea next door, suddenly the border, and Ethiopia’s claim over as much territory as possible, mattered a lot.

The Eritreans neatly reverse the argument. Ethiopia never really “owned” Eritrea; it simply replicated the Italian colonial model. Post-1945, the United Nations mandated federation between Ethiopia and Eritrea, but in 1962, the former proceeded with outright annexation, making the latter its 14th province. The imposition of Amharic, Ethiopia’s lingua franca, in Eritrean schools was not only a blatant example of Ethiopian colonialism, it also helped spark the war that would lead to independence [6], through a referendum supervised by the United Nations.

Despite a brief thawing of relations after Eritrea won its independence, the countries have been at each other’s throats for nearly two decades. You don’t need to take a stand on whether or how much Eritreans and Ethiopians resemble each other to notice a grim symmetry in their relationship. Both countries – democracies in name only [7] – support each other’s opposition movements, and fight a proxy war in Somalia: Eritrea supports the Islamist Shabab militias, while Ethiopia backs the fledgling Transitional Federal Government in Mogadishu.

Most recently, on March 15, 2012, Ethiopia sent troops across the Eritrean border to attack three bases of the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front [8], allegedly in retaliation for the group’s attacks on a tourist party inside Ethiopia [9]. This fueled fears of a sequel to the bloody Eritrean-Ethiopian war of 1998 to 2000, which cost between 70,000 and 100,000 lives.

That war was not only underreported, but also highly surreal: The linchpin of the conflict was Badme — a town that either doesn’t exist, or is located somewhere else, under another name.

The eponymous plain around the town is “relatively useless borderland” [10] between boundary rivers, the Mareb in the north and the Setit in the south. But it has become symbolic to both sides — a sort of East African Kosovo Polje [11] — because it is where the war started, in May 1998: Ethiopian troops killed some Eritrean soldiers near the border, and Eritrea retaliated by occupying the previously Ethiopian-held town of Badme. If the Eritrean regime had counted on exploiting the vaguely worded Italian-era border delimitations to their advantage, they had forgotten that most of the Ethiopian leadership, including the prime minister, Meles Zenawi, originated in Tigray, the province affected by the occupation.

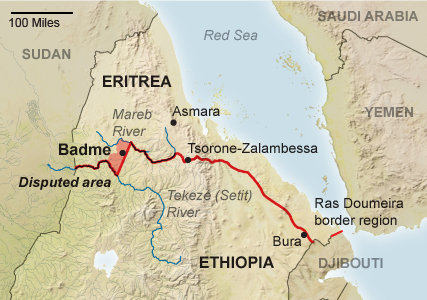

Ethiopia responded with “total war,” simultaneously attacking on several fronts, and bombarding the airport of Eritrea’s capital Asmara, which invited retaliatory air raids by Eritrea. In a regression from tactics of World War II to those from World War I, the air phase was followed by an intense phase of trench warfare. Thousands died in dusty ditches at Badme and other, smaller disputed areas further east: Tsorone-Zalambessa and Bure. By May 2000, Ethiopia occupied all disputed areas, and about 20 percent of Eritrea’s (uncontested) territory.

Eritrea admitted defeat. But Ethiopia clumsily managed to not capitalize on its victory. The loss of Eritrea in 1993 left Ethiopia bereft of direct access to the sea, and yet the regime in Addis Ababa did not even request access to an Eritrean port as part of an eventual settlement. All it wanted was Badme back.

Incredibly, in its final report in 2002 the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (E.E.B.C.) mentioned Badme just once by name, never even showing it on the map. This is because of confusion over what and where Badme is, exactly. Well south of the disputed border, clearly on the Ethiopian side, is a town called Yirga [12], founded in the 1950s by Ethiopians. The locals call it Badme, and that word is used also to refer to the wider plain on which the town is set. And that plain is divided by the disputed border [13]. In the old Italo-Ethiopian documents, the area remains totally unnamed simply because it was then uninhabited.

The E.E.B.C. reprised a straight line, unilaterally proposed by the Italians, as the international border, slicing off most of the disputed Badme Triangle for Eritrea. Ethiopia’s objections came too late, creating a fait demi-accompli: an international border that is the result of arbitration, but remains disputed by one of the parties involved. Ethiopia still occupies these and other areas that it claims are disputed rather than accorded to Eritrea.

This sounds like a fuse waiting for a fire. So why didn’t Ethiopia’s recent incursion kick off a Second Ethiopian-Eritrean War? Perhaps Eritrea didn’t hit back because the balance of force has tipped further in Ethiopia’s advantage. Ethiopia, with over 80 million inhabitants and a relatively robust economy, is an undisputed regional power. Eritrea, numbering barely 6 million, is suffering under crippling international sanctions imposed for its support of Shabab [14]. Maybe Eritrea is finally too poor, and Ethiopia too rich, to fight over a one-horse town. Or, maybe, the next round of fighting between these two Horn of Africa antagonists is still awaiting the proper spark.

Frank Jacobs is a London-based author and blogger. He writes about cartography, but only the interesting bits.

The New York Times

Agamino2001@yahoo.com March 29, 2012

who payed this fresh college student for this trash analysis.

SHINTI GHEMEL March 29, 2012

መንግስቲ ጣልያን እውን ምስ ጸላእትና ተሓዊሱ ። ነቲ ኢትዮጵያ ፣ብ15 ማርች 2012 ዶብና ጥሒሳ፣ ዝገበረቶ ገበን ፣ ዘወግዝ ጽሑፍ ኣቕሪቡ ኔሩ። ድሕሪ ኩነታት “ምምርማር” ግን አምባሳደር ሬንዞ ማሪዮ ሮሶ፣ ኣብ ኣዲስ ኣበባ ናብ ናይ ኢትዮጵያ ናይ ወጻኢ ጉዳይ ሚኒስተር ከይዱ፣ ብመርገጹ ተጣዒሱ ካብ መንግስቲ ጣልያን ዝተላእከ ናይ ይቕሬታ ደብዳቤ ኣረኪቡ። እዚ ንተግባራት ኢትዮጵያ እንቋዕ ገበርኩም እዩ ዝርኤ። ብናተይ ኣረኣእያ ንመንግስቲ ጣልያን´ውን ክንዋግኦ ይግባእ ይብል።

awet March 29, 2012

Folks, there is nothing seriously wrong with this article. It’s a fresh look at this stupid dispute. Only idots like Issaias would have wasted precious lives and resources, not to mention years, on the matter. If only somehow these criminal PFDJ would be deposed, we could have peace and security inour country.

Cambo March 29, 2012

It is well written article and describes the situation very well, except it exagerates a bit the “animosity” of what he called “between Ethiopians and Eritreans”. There is no animosity between the two people. The animosity is between the ruling political groups of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Many of us have wonderful Ethiopian friends and enjoy our social lives together. It is funny when we tell our Ethiopian friends how bad the Hgdef regime is, they retort back “… only because you don’t know how bad the Weyanes are.”

We both complain about everything as they do. We are both abused, enslaved and killed in the Arab world. Wherever there are Eritrean refugees, there are also many Ethiopians. They complain often when some Africans and non Africans ask them “Are you Eritrean?” as many of us do, “Are you Ethiopian?”

They complain how bad their soccer teams are which an Eritrean will respond “it has been years since we saw the last ball in Asmara.”

Otherwise, given its size, it is a good article made for a newspaper column. He gave it a perfect title for the upcoming cowboy movie about Badme “A one-horse town”.

He is rightly insulting us — how much idiots could they be to sacrifice more than one hundred thousand human lives for a dusty village?

aytbke endyu: zebkyeni zelo — bele seb’ay:

Perfect March 29, 2012

He is totally right.

I 100% agree with him.

He is also right about the animosity.

we can not deny that… there is hostility between these two people.

I am in Australia, i have never ever seen Ethiopian and Eritreans enjoy social lives together.

they are always on fire….

so this article is totally truth..

Dawit March 29, 2012

The reporter mentioned several reasons why Eritrea failed to respond in kind. But, he failed to state one prominent reason why Issayas did not attempt to retaliate and that is the troops moral and inability to see any future. No Warsay would fight for Issayas any more. Not only the moral is down but Eritreans are too smart now to fall for PFDJ’s cheap propaganda.