The Road Ends in Djibouti for Some Eritrean Refugees – By Dan Connell

The Road Ends in Djibouti for Some Eritrean Refugees Thousands of Eritreans are marooned in this desolate corner of the Horn of Africa. By Dan Connell, November 10, 2015. Temperatures were pushing 115˚ when we reached the crest

The Road Ends in Djibouti for Some Eritrean Refugees

Thousands of Eritreans are marooned in this desolate corner of the Horn of Africa.

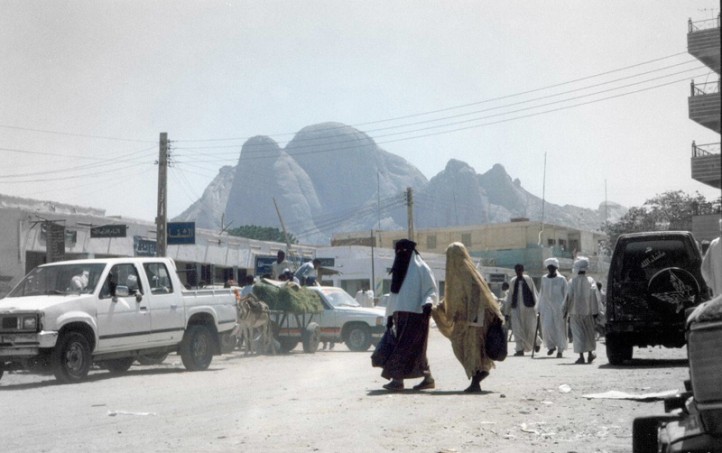

Temperatures were pushing 115˚ when we reached the crest of a rocky hill overlooking Ali Addeh, a desolate refugee camp on Djibouti’s southern border with Ethiopia and Somalia. Clumps of dull brown scrub dotted the ochre hills. Nothing stirred.

Once past the guard at the gate, we wound our way through a warren of houses patched together out of sticks, plastic, burlap sacks, and scraps of tarp to a community center where some 40 Eritrean refugees awaited our arrival. Mebrahtu, a camp elder, stood outside to greet us.

Otherwise, the parched dirt streets were empty. If I hadn’t known better, I would have thought the camp abandoned. As I soon learned, many residents wished it were.

Tucked away in a remote desert valley 30 kilometers from the nearest town, the camp was a cul de sac from which there was no easy escape. The guard was there as much to keep people in as to keep intruders out. Some of its 14,000 residents had been there since it opened in 1991.

Location, Location, Location

Djibouti, once a sleepy trading post, is now an independent city-state of out-sized geopolitical significance. It sits at a crucial crossroads between the volatile but strategic Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. It provides the main port of entry for goods destined for land-locked Ethiopia. It also hosts French, Japanese, and American military bases.

Refugees and migrants pass through it from virtually all directions. The latest influx comes from across the Red Sea in Yemen, a result of that country’s collapse into civil war earlier this year. Before that it was fed by the disintegration of neighboring Somalia.

But there has also been a steady flow of Eritreans.

First came those fleeing oppression and war during the years it was under Ethiopian occupation. In the second wave, Eritreans were escaping a cult-like dictatorship put in place by the movement that secured the country’s independence in 1991. Among those arriving now from Yemen are Eritreans who sought sanctuary there decades ago and are on the move again.

I was there to record their narratives as part of a yearlong investigation of the Eritrean refugee experience that took me to 19 countries on five continents. Mebrahtu had collected more than 40 refugees at a small community center at the heart of the camp.

Crammed together on rickety wooden benches under the corrugated zinc roof, all but one of my hosts were men — most of them former soldiers. They’d come to tell their stories.

War Stories

Hermon, 37, had been called up for the required 18 months of national service in 1996. But he was kept in the army when war erupted with Ethiopia in 1998 over a minor border dispute and was never released. He said he stayed until 2011 out of fear that his family would be punished if he fled. But finally, losing all hope of release, Hermon escaped. “We were kept like slaves,” he added.

Ghebreab, orphaned as a child, was only 15 when the border war broke out and he was called up, never to be released. Nor did he get to finish school. He said that he put up with this until he heard that the authorities had come to his house and arrested his younger brother. When he asked his commander for an explanation, he was hung by his hands in the hot sun for 100 hours and warned that he would be killed if he asked again. That’s when he decided to flee. He made it out in 2011, walking into Djibouti under cover of darkness.

Amanuel, 43, was initially exempt from national service due to a disability, a deformed right leg. But he was called up in 2006 after being caught in a raid on a clandestine Pentecostal Church, which had been banned four years earlier, along with other evangelical denominations. He said he was sent to a desert training camp as punishment.

He crossed into Djibouti in 2011 and, like the other two, was immediately arrested as an enemy combatant — for Djibouti, too, had fought a brief war with Eritrea that had yet to be fully resolved. All three were released last year and sent to Ali Addeh.

Mebrahtu himself had been jailed twice in Eritrea in the first years of a sweeping crackdown on dissent after the border war. The first time he was arrested for trying to escape to Yemen. The second time, jailed for questioning party leaders about state control of the economy, he was tortured for five weeks to get him to give up names of those who shared his outlook. He said he was released after being forced to sign a confession that could be used to re-arrest him at any time. Soon after this, he fled his post and hid in the capital. It took him almost 10 years to scrape together the money to be smuggled out.

A Tigrinya speaker who had grown up in the port of Assab, he commanded respect among all segments of the refugee community and seemed more concerned with keeping up the spirits of others than with his own travails. His main worry was the increasing harassment of Eritreans by Islamist extremists in the camp — that and the creeping despair that ate away at many as one bleak day bled into the next.

Apart from a handful of positions filled by refugees at the small camp clinic or the Lutheran-supported primary school, there was almost no work available at Ali Addeh. So most residents passed their days idly, hoping their names would eventually come up for resettlement to a third country.

Small wonder that those consigned to live here feel trapped and forsaken. “I have no future here unless I die,” said one.

Zahara’s Story

Zahara, 26, was one of the fortunate few. She had one of those jobs and was grateful for it. But she said she never gave up hoping that things would change in Eritrea and she could go home again.

She, too, had done her 12th year of secondary school at a military training camp, but after scoring well on her exams, she was sent to nursing school. Nevertheless, she was growing disillusioned with the regime and disturbed at the sexual harassment she’d suffered. In 2009, while in the frontier town of Tessenei for her practical training, she and four other trainees tried to flee to Sudan.

She said she fled because she was being forced to do demeaning domestic chores for officers while fending off their sexual advances. She was one of two girls in a five-person group that slipped out after dark, days after a group of 13 girls sent word back that they had made it. However, her group was followed and chased, and she was caught.

Zahara and the other girl were held briefly at the Ali Ghidir agricultural office and then transferred to the Prima prison at Barentu, not far from their nursing school. A month later, they were moved to the notorious prison at Adi Abieto in Eritrea’s central highlands.

During that time, she said, she saw “many terrible things,” including frequent beatings of both men and women. The men were mostly hit with wood or metal rods on the soles of their feet until they were unable to walk. Women were beaten about their upper bodies, often on their arms as they sought to protect themselves. Some were mothers of escapees being interrogated about their children’s flight. She said she saw some die.

Zahara drew on her elementary medical training to treat their wounds, which was appreciated by her superiors. After eight months, she was taken to a military court and quizzed on her escape attempt. She said the only questions they asked were: “How did you do it? Who knew about it? Who helped you?” She told them they had conspired among themselves only, and she was sent back to the nursing college.

In 2011 she was assigned to the Orota Hospital in Asmara, where there was a shortage of trained personnel. But she remained under heavy travel restrictions and was not permitted to visit her family in Assab. Nor was she paid for her work, she said — not even pocket money — as she was still being punished for her escape attempt and was effectively under house arrest.

After another year and a lot of complaining, she was given a short leave to attend what she insisted was an important family wedding. Once in Assab, however, she met soldiers she knew from her training and quickly made plans to leave — with the soldiers.

As soon as they crossed into Djibouti, they were taken prisoner by border guards and sent to the gendarmerie for questioning. There were five in the group — three boys and two girls. The boys were suspected of being in the army (which was true) and were taken to prison. The girls were sent immediately to Ali Addeh.

Today she works as a nurse at the camp clinic, but she’s paid only a third what Djibouti citizens earn for the same work. This, said other refugees, is standard practice within the camp. But Zahara isn’t complaining. She accepts it because at least she’s working. Sitting idle would be worse.

wedi Ken November 11, 2015

God bless you Dan for everything you do on behalf of Eritrea & Eritreans!

The future democratic government of Eritrea needs to officially recognize you with a medal of honor, at the very least!

Haben November 11, 2015

Wedi Ken brother, I agree 100% with everything you said but can we please give this great gentleman a special Eritrean local name because he may look white and he might have a white man’s name as well but deep down he is truly wedi Erey shikor anbessa. God bless him and an Eritrean noble prize would be his in the next free and democratic Eritrea.

k.tewolde November 11, 2015

The voice of shattered dreams continues………

goytom November 11, 2015

ENTAYMO KNBL! the horrible stories never stop. from one hell hole into another hell hole. i feel bad for them. i’m powerless to do anything else, you have my sympathies yehwatey.

amare L. November 11, 2015

Thank you Dan Connell, once you were called a friend of the revolution. and now you are the friend of the people. keep up your good job.

AHMED SALEH November 12, 2015

Well said , he was also victim of 03 propaganda machine of

Issayas like every body else . But at least he didn’t gave

up on Eritrean people true desire for justice and peace .

I wish those educated Eritreans who had close relationship

with Issayas at time of revolution take the walk of solidarity

with Eritrean people like Dan Connell .

Tired of politics talk , I respect men who prove with action .

yo November 11, 2015

One thing you have no evidence that he is a CIA or if he still supporter of Esayas. Another thing according to you either he is a CIA or Esayas supporter. Unless you claim Esayas is also CIA, Which is ridiculous, He can not be both. If you have any evidence prove it. If just a fantasy of yours created to suit you. Secondly, who cares what he is or what he was, he is not saying make me a leader, he is just reporting about Eritrea refugees in Djibouti. As long as I know he is historian, regardless of his intentions I read or listen his narrative. I make my own judgment.

Natnael November 12, 2015

@yo, why do you mean “..is ridiculous,…” ? Politics can be dirty and has neither border, moral, conscience, …etc. In politics everything possible and the duration of friendship or enemty is very variable, from short to very long. One thing is true, I make my own judgement too! Despite my relatively active participations in the Cyber-discusions about the condition in Eritrea, I know too little about Dan Connell and the subject. It is very hard to have the right overview of the really conspired developement of our beloved country and the HORN of Africa.

AHMED SALEH November 12, 2015

Dan Connell was a friend of Eritrean people at times of revolution

and he stands firm in solidarity with people verses the leadership to

fight for the promise of our martyrs that he witnessed first hand in

the field (medda Eritrea ). Regardless our complicated political

skirmishes he expressed his concern on dangers civilians face under authority of a person who deceived the world with false impression .

In fact no matter what “A FRIEND IN NEED A FRIEND IN DEED” , goes

the sayings. I wish many follow his example for the sake of those

poor souls at bad conditions in refugee camps .

Asmara Eritrea November 12, 2015

The above story demonstrates Dan’s long standing commitment and friendship with the Eritrean people. Having read most, if not all, of Dan’s books on Eritrea, I feel really blessed that Eritrea has such a wonderful and a true friend. Don’t despair, Dan, keep doing the right thing and the truth will eventually prevail – as it did with the independence of Eritrea. Isaias is in his last legs – not much to go now!

Eritrea forever, death to dictatorship.

Aziz Tewil November 14, 2015

Thank you very much Tegadalei Dan Connell. You once again show your dedication to justice and humanity. You are giving a voice to the voiceless, wheras most of the educated Eritreans are watching the atrocities of the dictatorial regime silently. Keep up your good work.

Aklilu November 17, 2015

Little is said about the great works of Dan Connell. We have no enough words to thank him. Just heartily thanks and may God bless you and your family.

Berhe Tenesea November 22, 2015

Dan Connell, is the true friend of Eritrea,. In the new that is coming Eritrea, he must be given citizenship and the respect he deserves.

He knew Eritrean politics for a long time and he was like a fighter or teghadalay.

Eritreans will not forget his valuable contribution.

Long live Teghadalay Daniel.